‘Orunodoi’: How To Tell A Story The Right Way Amid Tech-Tonic Shifts

As print journalism is gradually losing its relevance, can the digital media recapture the possibilities of the written word and tell the untold stories from the Northeast in the old-fashioned way but in new formats?

Siddhartha Sarma

Commemorating a milestone in literature is a complex task. Commemorating one in journalism is much more so, mainly because journalism as understood today is about constant motion, a continuous news cycle, about a great degree of heat and very little light. It has become a creature of great appetites which must be constantly fed, and as with all omnivorous diets, quality might not be a significant consideration.

Newspapers and magazines are important only as long as they churn out content. There is no term as tragic for those who earn a living from the written word as ‘defunct publication’.

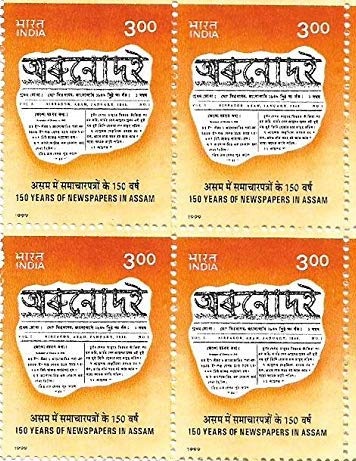

Only a few such publications can claim a legacy beyond their lifetimes. Orunodoi, the first local-language magazine in the region, and the first in Axomiya, was much more than just a pioneer. The intervening 175 years since it was first brought out show us what could have been, and what happened.

It was a period of great change in the subcontinent. Assam had only recently been included in the political map of India. Language had become a political tool in a very modern sense. Orientalists like the great naturalist Brian Hodgson, who believed education for Indians should be in their respective first languages and not in English or dead classical tongues, had retreated in the face of Thomas Macaulay and his energetic allies.

The political repercussions of this can be felt even today. If there was ever a possibility that languages could be promoted without mutual ill-feeling or prejudice, if there was ever a model where mother tongues could flourish, the colonial apparatus ensured this would never come to pass. The post-colonial apparatus merely inherited the colonial desire for political hegemony through one language, a ‘national’ one at the expense of ‘regional’ languages.

So Orunodoi was from the very beginning much more than a publication by a group of Baptist missionaries. It was much more than a collection of Christian tracts, news from around the world for the edification of a small local educated class, and the leavenings of science. Its existence was a statement that each small part of India, particularly in the periphery, had a voice and an intellectual wellspring that was rich and deep. Orunodoi was about possibilities.

Among the factors which led to the magazine’s influence on subsequent literature and journalism in Assam were the extraordinary abilities of some of its earliest contributors. Consider Nidhiram Keot, who came from no particular background in a village near Gohpur, but who flowered at the Baptist mission in Sadiya.

By 1845, he had been baptised and had translated the Bible into Axomiya. His Khristiyo Dharmageet was the second Axomiya Bible, and he believed the first — a joint work by William Carey and Atmaram Shorma — had linguistic shortcomings because of the extensive use of Sanskrit and Bangla words. This was not so much about purism — the first contributors of Orunodoi had very little to do with isms — but about loyalty to their lived experiences. Arguably the first real prose writer in Axomiya, Keot (or Nidhi Farwell as he is better remembered today) also wrote the first law book in the language.

This understanding of the significance of the mother tongue, of literary merit and political awareness that we see in his life and works, and in the first contributors to Orunodoi, was inherited by the generations of scholars, writers and political commentators who came after those pioneers.

Somewhere down the line — and we can mention the technological milestones which contributed to this — print journalism began its long retreat from these ideological and intellectual moorings. It began to compete with TV in bringing information to the reader in ever-shorter news cycles; an impossible task and an unnecessary one. In the process, an artificial divide was created between journalism and narrative structures, between the underlying meaning of the news story, the significance of informed opinion and the felicity with the written word which brings journalism and literature together.

The possibilities of the written word, which Nidhiram Keot understood so well, are now articulated in silos which are not expected to converge. The expert despairs that the journalist will ever explain the complexities of our world properly; the journalist seeks the pure id of the hive mind as witnessed in the wildernesses of Twitter, and the writer believes the incoherence of the breaking news ecosystem has no space for genuine storytelling. The loss is the reader’s. The loss is also the print journalist’s. And this loss extends across languages, when functionally bilingual writers could have had access to a range of worldviews, as the Axomiya journalists of the 19th and early 20th centuries did.

Here in The Northeastern, we are a little old-fashioned in our approach (but not to tech). Our goal is to recapture the possibilities of the written word, to work beyond news cycles, beyond the silos that journalism schools and the ‘national’ media believe in so utterly, to tell a story as it should be told through the written word, supplemented with photojournalism as it was always intended to be. We may not attain the commanding heights of Keot and his inspired contemporaries, but we owe it to them, and to you, to tell stories the right way.

(Siddhartha Sarma is an award-wining novelist and journalist. His latest work of fiction, Twilight in a Knotted World was published by Simon & Schuster last year.)